Virtual Production

WHAT IS VIRTUAL PRODUCTION?

Over 50% of major studio films now use virtual production techniques, blending real-time 3D environments with live-action footage.

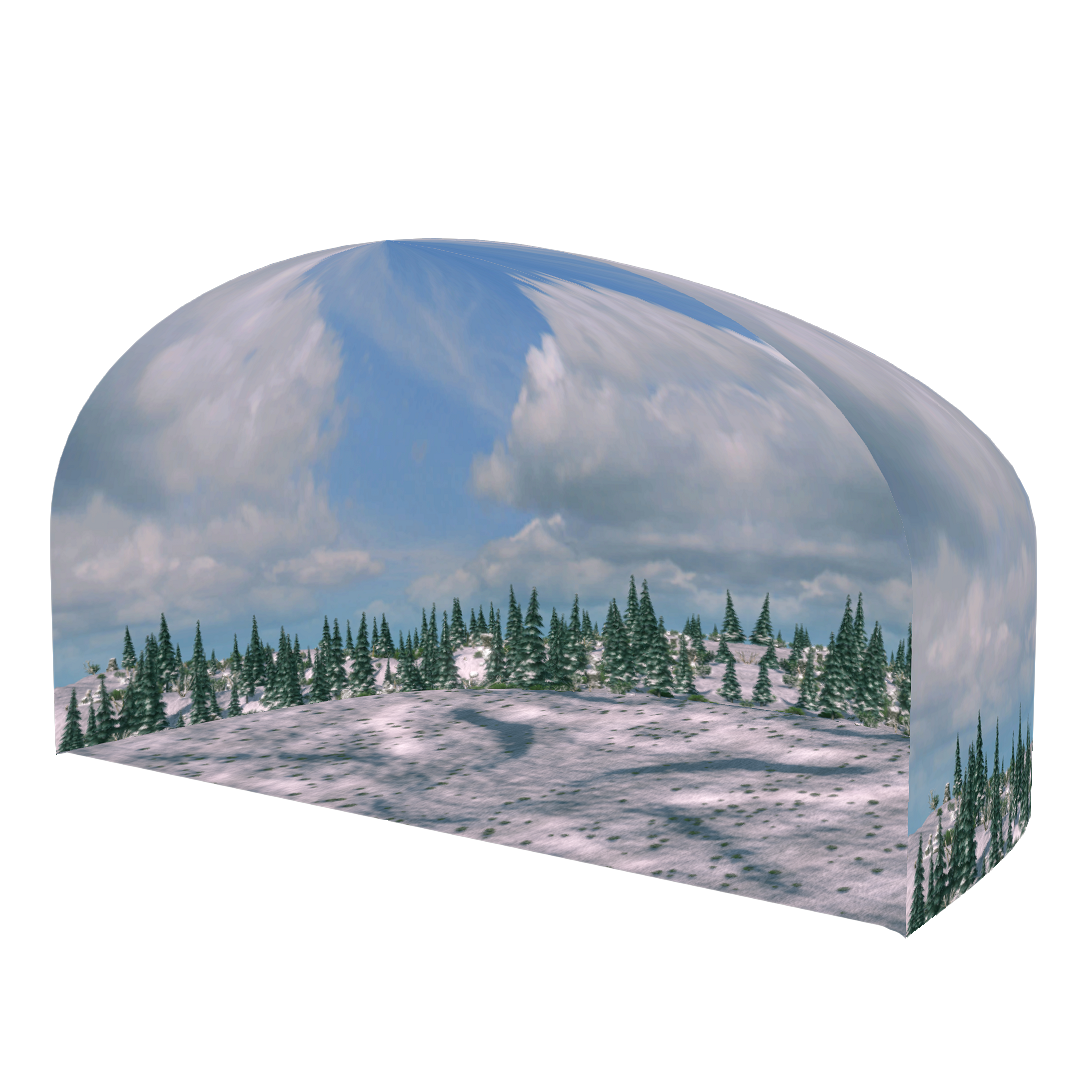

Virtual production is reshaping filmmaking, by merging live-action performance with real-time digital environments. Using technologies like LED volume stages, motion tracking, and real-time rendering engines (like Unreal), filmmakers can immerse actors directly into virtual sets, allowing for immediate visual feedback and reducing reliance on post-production (Barnett; Bodini; Silva Jasaui). This approach, which evolved from traditional green/blue-screen techniques (and even older techniques like rear-screen projection), enables faster iteration and more realistic lighting interactions, offering greater creative flexibility in filmmaking (Liu; Camille; Frank; Willment).

However, virtual production also presents challenges. It requires significant investment in specialized equipment and skilled artists, which can be a barrier for smaller studios (Swords; Azzarelli; Boutellier; Zhou). Additionally, the shift from post-production to pre-production problem-solving demands close collaboration among directors, cinematographers, and technical teams to coordinate complex setups. Despite these hurdles, virtual production is rapidly gaining traction, with the global market projected to reach $6.8 billion by 2030, reflecting its growing adoption across the industry (Grand View Research).

| Technology | First Use | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miniatures & Models | 1902 (A Trip to the Moon) | Scale models simulated large environments or vehicles with realistic lighting and perspective | 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Star Wars (1977) |

| Matte Paintings | 1907 (Missions of California) | Artists painted detailed backgrounds on glass or canvas to extend sets and create worlds too costly or otherwise prohibitive to build | The Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz (1939) |

| Rear-Screen Projection | 1930's (popularized by films like King Kong in 1933) | Actors performed in front of a screen with pre-filmed footage projected from behind — an early form of compositing “live” action and background | Driving scenes in North by Northwest (1959) |

| Optical Compositing & Blue/Green Screen | 1940's | Filmmakers combined separate film elements in the lab, later replaced by digital chroma key (green/blue screen) methods | Flying scenes in Superman (1978) |

| Front Projection | 1950's | A reflective screen behind the actors allowed brighter, sharper projected images | Background environments in Interstellar (2014) |

| Motion Control Technology | 1970's | Computer-guided cameras repeated precise movements for layering multiple passes, which was crucial for VFX integration | Hoth sequence from The Empire Strikes Back (1980) |

| Digital Compositing & Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) | 1990's | The shift to digital allowed seamless integration of live and virtual imagery without the physical requirements of analog methods | Dinosaurs from Jurassic Park (1993) |

| Real-Time Virtual Production | 2010's | LED walls, performance tracking, and game-engine rendering unite actors and digital worlds on set | Driving scenes and cityscapes from The Batman (2022) |

Zhou's (et al.) “Sophia-in-Audition: Virtual Production with a Robot Performer” explores how the humanoid robot Sophia can act as a virtual performer within a high-tech, multi-camera lighting dome. The study stands out for combining robotics, motion capture, and cinematic lighting to test how audiences respond to a robot actor, and for sharing valuable datasets for future research. While its setup is specialized, it marks a a step in merging physical and virtual performance spaces. Anyone interested in modern virtual production and the future of digital performance (even outside of film/TV) should take a look at this paper for its creative and technical insights.

PROS OF VIRTUAL PRODUCTION ^

The Mandalorian (2019) was the first major production to use ILM's LED volume StageCraft technology for virtual sets.

One of the standout and often overlooked advantages of virtual production is its potential for environmental sustainability. Traditional film shoots often require large crews, extensive location travel, and energy-intensive lighting setups. By shifting scenes to LED volume stages or virtual environments, productions can drastically reduce travel, construction, and on-set power consumption - while still achieving realistic and immersive visuals (Barnett; Frank; Sawicki). This also allows filmmakers to iterate quickly without committing to costly physical sets that can be scrapped or abandoned, further reducing waste.

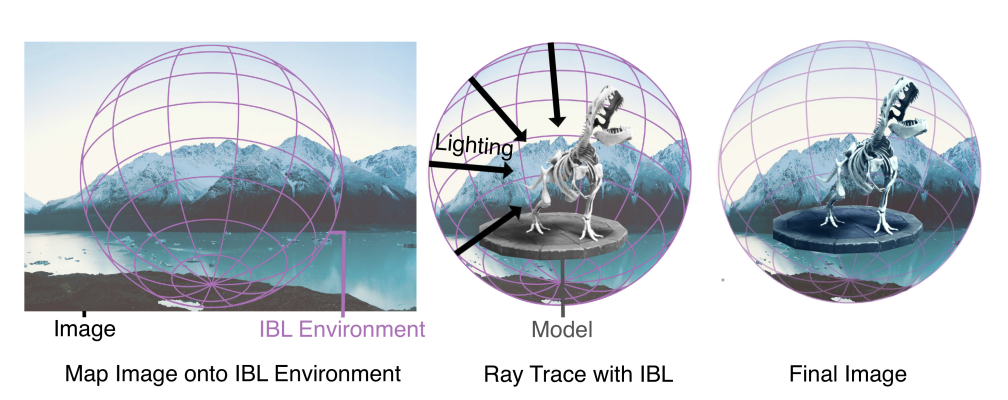

Additionally, the mere technological realism and flexibility of virtual production has grown rapidly in recent years. Real-time rendering engines and LED volumes provide actors with interactive, photorealistic environments, enabling more natural performances compared to traditional green-screen setups or motion capture alone (Camille; Bodini; Silva Jasaui). LED volumes also offer organic, situational lighting, where the virtual environment itself lights the actors and sets dynamically, producing more realistic and cohesive images on camera. This integration of multiple disciplines — film, VFX, and even game design — has in turn fostered new creative workflows where artistic and technical teams collaborate more closely, often improving both speed and quality of production (Willment; Azzarelli).

Another major benefit is the increasing incorporation of AI and intelligent cinematography. Tools that assist with camera tracking, scene composition, and even virtual performers (e.g., Zhou’s "Sophia-in-Audition" project) allow filmmakers to explore shots and sequences that would have been prohibitively expensive or logistically impossible in the past. AI can also enhance previsualization, lighting simulations, and automated compositing, giving artists a lot more time to focus on storytelling (Azzarelli; Frank). Beyond traditional film and TV, these technologies are finding applications in things like live events, education, and simulation training, where interactive, real-time virtual environments can teach, engage, and entertain audiences in innovative ways (Boutellier; Frank).

Finally, the LED volume itself serves as a compelling data-driven tool. By using real-time cameras and tracking systems, productions can visualize exactly how scenes will look in post-production while filming, minimizing guesswork and allowing immediate adjustments to lighting, camera angles, and scene composition (Camille; Silva Jasaui). This immediate feedback loop not only improves efficiency, but also empowers directors and cinematographers to make more informed creative choices on set.

This article from Jon Swords and Nina Willment compellingly argues that virtual production is reshaping film and television by shifting major creative and technical labor from post-production into pre-production. The authors use the “production network” lens to map how real-time capture and LED/volume workflows are altering traditional roles, business models, and even power dynamics across the industry. The strength in this thinking lies in combining theorization with actual practice in this pivot from “fix it later” to “fix it now.” While most of the focus is currently on high-end production networks, the implications are broader - that smaller productions and future media forms might have to rethink their workflows if they want to stay current with changing technologies and tastes. For anyone examining how virtual production is changing not just tools, but organizational structures and workflows, this article is a must-read.

CONS OF VIRTUAL PRODUCTION ^

On large LED stages, data streams for lights, textures, and camera tracking can exceed 1 TB/hour.

While virtual production offers wide creative flexibility, it also comes with significant technical and logistical challenges. One major concern is the heavy reliance on real-time game engines like Unreal Engine, which has created a knowledge gap in traditional VFX education/previous required knowledge and modern workflow practices (Barnett; Boutellier; Swords). Many emerging filmmakers and crew members now need expertise in both cinematic storytelling and interactive engine operation, which can create barriers for smaller teams or those trained in conventional film/TV pipelines. This technological dependence also extends to LED volume setups, where the rendering, capturing, and “dressing” of large-scale displays demands extensive preparation, hardware resources, and testing — all tasks that are both time-consuming and expensive (Camille; Silva Jasaui; Sawicki).

There are also spatial and perceptual limitations inherent in LED-based virtual environments. Camera movements for ceilings, floors, and wide angles can be restricted by the physical size of the LED stage, which can then affect the realism of shots and potentially limit cinematic freedom (Iseli; Liu). In addition, some subtle visual cues, like depth perception or peripheral lighting consistency, may not translate perfectly through a virtual stage, which could impact audience immersion if not carefully managed (Virtually Real; Bodini). These limitations mean that despite the promise, virtual production doesn't fully replace traditional filmmaking techniques, particularly for productions with complex spatial demands or highly dynamic camera setups.

Another consideration is that much of the creative work now shifts toward pre-production, effectively moving tasks that were usually post-production into the planning phase (Swords; Frank). Directors and VFX teams often finalize the look of a scene digitally before shooting, which can reduce the spontaneity and iterative decision-making that occurs on a traditional, physical set. The technology is powerful, but it imposes a new workflow that can be inflexible and heavily dependent on highly skilled artists and expensive infrastructure (Willment; Azzarelli; Zhou).

Finally, technical requirements — things like high-performance GPUs, real-time rendering rigs, and large-scale LED walls — pose both cost and accessibility barriers. Smaller studios may struggle to adopt virtual production fully, and the resource demands for high-quality output can sometimes outweigh the efficiencies offered by shooting in a more controlled virtual environment (Sawicki; Silva Jasaui). These challenges illustrate that while virtual production represents a remarkable evolution in filmmaking, it isn't without its trade-offs in cost, technical complexity, and creative constraints.

Artists create a 3D scene in Unreal Engine (or similar)

The physical camera’s movement is tracked in real time

The LED walls display the updated 3D scene

LEDs cast realistic lighting onto actors and props

Final shots blend real and virtual elements instantly

Azzarelli’s “Intelligent Cinematography: A review of AI

research for cinematographic production” surveys how AI is being applied to cinematography, including camera motion, placement, and scene capture across live, virtual, and aerial productions. The paper is highly technical, covering topics from automated calibration to generative AI, but its real value lies in mapping the current state of research and highlighting opportunities for innovation in virtual production. If you're curious about how AI and intelligent tools are shaping modern filmmaking workflows (especially in hybrid physical/digital environments), this paper offers a comprehensive and insightful overview worth looking into.

IMPACTS AND OVERVIEW ^

Real-time camera tracking can produce over 500,000 positional data points per second on set.

Today, virtual production is increasingly becoming a standard part of both blockbuster and independent filmmaking, with rapid technological improvements hinting at an even broader adoption in the near future (Barnett; Willment; Bodini). As real-time rendering engines, LED volumes, and AI-assisted cinematography evolve, productions can achieve higher visual fidelity with faster turnaround, enabling directors to experiment more freely with lighting, camera angles, and scene composition. While the technology is still maturing, the trend is clear: virtual production will not replace traditional filmmaking, but it will continue to expand the creative toolkit, offering options that were previously impractical or impossible (Silva Jasaui; Frank).

Beyond film and TV, virtual production is showing promise in live events, education, simulation training, and other immersive experiences (Boutellier; Frank). Interactive virtual environments allow audiences to engage with content in new ways, from live concerts with real-time background simulations, to educational programs where learners can navigate realistic scenarios safely. These applications demonstrate that the benefits of virtual production extend well past entertainment, offering innovative workflows for whatever industries that might require real-time visualization and collaboration.

In terms of workflow, virtual production has improved pipeline efficiency by allowing for more iterative and integrated collaboration between different creative departments (Willment; Azzarelli). Previsualization, lighting, and compositing can be adjusted on the fly, reducing costly re-shoots or post-production fixes. The ability to combine VFX, film, and game design principles creates a more interconnected production environment, though it also emphasizes the need for multidisciplinary skills and continued R&D to optimize tools and processes (Barnett; Swords; Zhou).

Despite the advantages, virtual production still sparks philosophical and practical questions about cinematic realism. What makes a film “real enough” when entire worlds are artificially rendered? Does audience immersion depend on physical authenticity, or on perceptual plausibility and narrative engagement? Writers like Iseli and Bodini suggest that while perfect realism may not be necessary, the perceptual and emotional cues enabled by LED volumes and real-time rendering seem to be sufficient in convincing viewers, provided the creative choices support the story.

The evolution of virtual production seems inevitable, with incremental improvements in engine fidelity, AI assistance, and interactive stage technology likely to reduce current limitations. While challenges remain — cost, spatial constraints, training requirements, and workflow integrations — the technology continues to introduce possibilities for filmmakers, providing unprecedented flexibility and creative control. In short, virtual production is not a replacement for traditional filmmaking, but a transformative tool that expands what directors, cinematographers, and VFX artists can achieve, all while opening doors for broader applications outside the traditional screen-based media landscape.